How one Engineer is Challenging the Lack of Representation in her Industry

Author: Naliaka Odera

“95% of the time, I love my job,” electrical engineer Martha Wakoli explains. “I love the idea of thinking about things and creating them, and seeing them come to life. It’s a wonderful gift. It’s almost like being a composer.”

Martha, the Founder of Queengineers, an online publication that celebrates Kenyan women in engineering, tends to face obstacles head-on. From when she was quite young, Martha always wanted to know why things worked the way they did. In school, she gravitated towards physics and saw the example of her father’s own career as an engineer as inspiration for how she could marry all her favourite subjects together when it came time to forge her own path.

The reality of lack of representation in the field of engineering hit her swiftly at the University of Nairobi. “In my first year, there were 170 of us students and there were only 25 girls.” That moment is when the seed was planted for Martha to do something about the lack of diversity in her field. “In the five years that I was at university [studying] in Electrical Engineering, I never had a female technician or professor.”

The final straw for Martha was when she took a job as a field engineer shortly after graduating, and they did not have a ladies washroom. “I had to have a couple of uncomfortable conversations with HR for them to reconfigure, or refurbish some toilets for my use.”

Martha is by no means a minority in this experience. The Harvard Business Review in a study looking at why fewer female engineers in America stay in the field than men, post graduation, concluded that many women begin to experience discouraging discrimination in their first job experience. The women surveyed reported increased gender stereotyping with role assignation, infrastructural systems that favoured men over women, and harassment.

Martha found that her experience in Kenya was similar, “You can go to work and find there aren’t toilets for you, you have not been considered in any of this, or you can enter a meeting with a male technician and he is the one who is addressed as though he is in charge. The work-world is definitely less accommodating. I have now worked in several different places and something that keeps coming up is that I will either be the only female in the technical team, or in recruiting for technical roles, we will only interview men.”

In typical Martha fashion, she began to consider how she could address the lack of representation in her field. Martha broadly considers the issue as two-fold; firstly there are fewer women signing up for engineering in school, and secondly, that there are fewer women being recruited for engineering jobs.

A 2020 survey conducted by the Kenyan networking association Women In Real Estate, entitled “Women In the Built Industry”, revealed that although the numbers of female engineering graduates have increased, they still only account for 10.6% of engineering graduates. In the construction industry, out of a total 17,119 registered construction engineers, only 2,645, 15%, are female.

In terms of the lack of representation in job recruiting, Martha describes it as a “filtering problem” that needs to be addressed. The fact that men are always offered new roles first is part of “company culture,” she explains. Now that she is in a position where she often interviews and recruits junior engineers, Martha is deliberate in ensuring that she provides women engineers with as much opportunity as possible.

While there is not much in-depth research on how societal or culturally influenced discrimination affects women engineers in the workplace, there are a few studies on how they have impacted women in universities, leading to both fewer women signing up for engineering degrees and an increased number of women not completing their courses. Writing for The Conversation, Lucy Wandiri Mbirianjau, a Lecturer at Kenyatta University in the Department of Educational Foundations, addressed the societal and infrastructural biases that do not support women engineers. Specifically, she outlines the cultural implicit bias that frames STEM subjects as inherently masculine and the lack of institutional support afforded to women who fall pregnant while students.

But these hindrances have not made Martha waver from her goal of increasing representation, they have only further encouraged her on its necessity. “For me, it is more of a rational argument than an emotive one. It is illogical, for us to continue to act as though half the world does not exist. It denies us all the opportunity to evolve faster.”

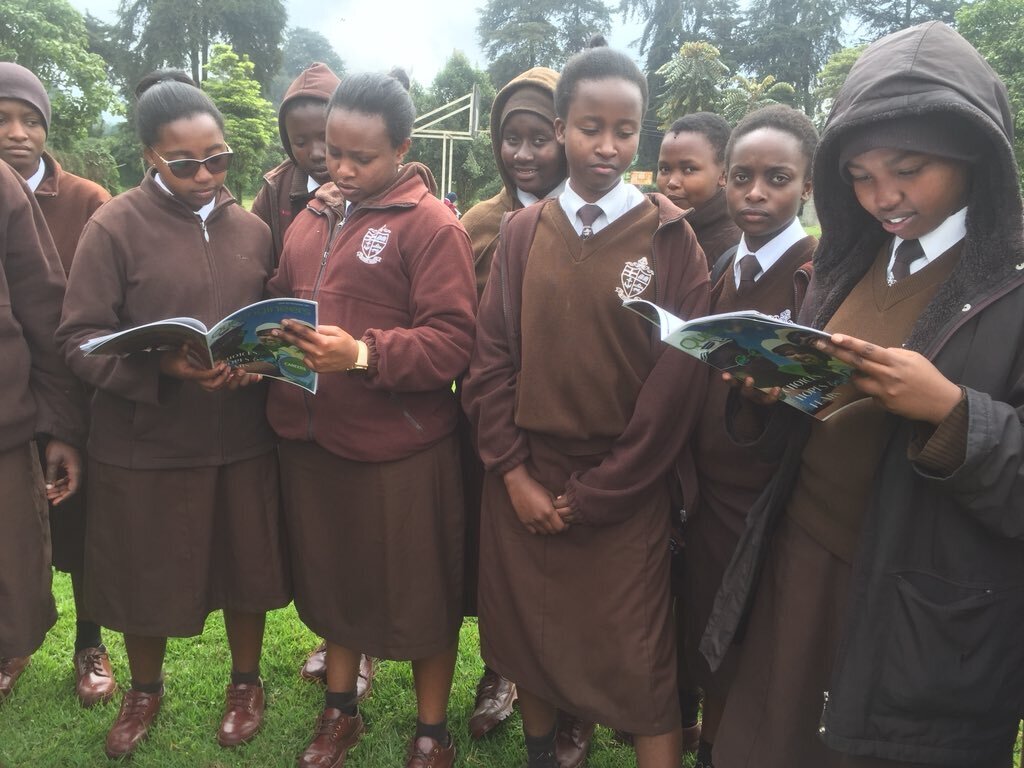

Through Queengineers, Martha and her friend and partner Marian Mutui, highlight the stories and experiences of Kenyan women in Engineering. Demystifying who can be an engineer has become an integral part of the conversation Martha has been having with young girls and women who are considering this career path. Now, many of the women who have been featured in Queengineers are acting as mentors to other young women hopefuls.

Martha is fuelled by an urgent, optimistic, passionate drive for equality. Now that she has been able to see the lack of representation within her industry, her engineering brain is working hard to address the flaws.“What our platform is doing is pointing out the obvious flaw in the design. When we think about infrastructure in this country, and consider the lack of female lead engineers... It explains, for example, how we can have whole automated buildings, with automated doors and lights, but the sanitary bin, which is quite unhygienic, is still not automated in many office buildings. When we lack female contributions in our industry, we are hurting ourselves, and the ability to optimize every facet of life.

“It’s not just about more women being in school anymore. It’s that women’s contributions should be taken more seriously, and faster, like the time is right now. My hope is for my work to be obsolete. That we never again have to create a catalogue where little girls need to be told that they can do anything.”